Semipermanence

One of the most interesting contributions to this year’s Biennale di Venezia is with no doubt Rahul Mehrotra and Felipe Vela’s research on “ephemeral urbanism”, which brings to the fore several issues linked to the design and management of temporary settlements such as Black Rock City or the gigantic Khumb Mela. This text by Master student Aziz Bahou investigates a related, and extremely urgent topic, which is the possibility (and necessity) to improve the spatial conditions of refugee camps by recognising and implementing their urban, rather than military, character. DTF

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp, Jordan

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp, Jordan

A case for strategized design of refugee camps

In his book Camps: A Guide to 21st-Century Space Charlie Hailey organizes camps into three different categories: Autonomy, Control and Necessity. Refugee camps fall into the third category: Necessity; which “explores transient spaces of relief and assistance. Camps of necessity respond to the power of circumstance. They are lodged between autonomy and control. Camps of necessity are also sites of negotiation between external planning and long-held nomadic practices.” (Hailey 16)

Refugee camps are often called Displaced-person (DP) camps and have existed since 1901 when they were invented by the British in South Africa (and called ‘concentration camps’) as a place to hold Afrikaner women and children whom the British had burned out of their farms, because they supported Boer commandos. The camps never worked as communities; instead they became places of dependency, control, destitution, and disconnection from any sort of normalcy. (Ledwith and Smith, 6)

Modern DP camps are soon-to-be permanent cities and the notion of them being “temporary camps” is becoming a fiction. Average DP camps exist for 17 years, stumbling the generation of children who grow up knowing nothing of the world their parents left, or the world they will arrive into. (Ledwith and Smith, 6) For example Burj el-Shemali Camp in Tyre, Lebanon, which was established temporarily in 1948 to house Palestinian refugees from the first Arab-Israeli War, is still in existence today and has around 20,000 registered refugees. (UNRWA)

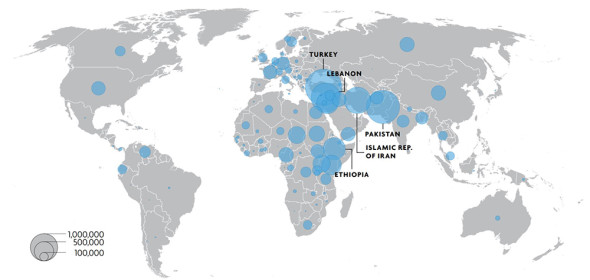

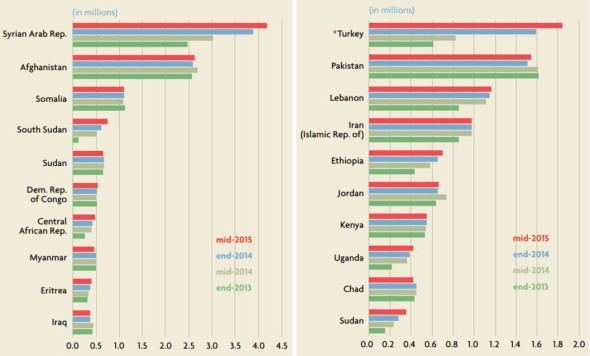

The total number of refugees has increased significantly over the last five years to reach an estimated 15.1 million worldwide (mid-2015 census), its highest level in 20 years. The main contributing factor is the war in the Syrian Arab Republic in addition to armed conflicts or deterioration of ongoing ones in Afghanistan, Burundi, Congo, Somalia, and Ukraine, among others. (UNHCR)

It has also been in the news that the number of asylum applications in Europe has increased sharply and there’s controversy of how this increase has been dealt with. Despite the high numbers and the wide media coverage of asylum seekers in or on their way to Europe, these numbers are still insignificant in comparison to refugees flocking to countries in the Middle-East and Africa.

Below are statistics courtesy of the UNHCR depicting the increased numbers in refugee influx in the Middle-East and Africa.

Refugees Host Countries, mid-2015 (UNHCR)

Refugees Host Countries, mid-2015 (UNHCR)

L: World’s Refugees’ Countries of Origin. R: World Refugees’ Host Countries (UNHCR)

L: World’s Refugees’ Countries of Origin. R: World Refugees’ Host Countries (UNHCR)

The refugee situation in the last five years has been documented in the media from a socio-political point of view and rarely from a spatial and/or planning point of view. The predominant notions of how refugee camps are portrayed in today’s media landscape are (Herz 9):

1) Refugee camps are seen as humanitarian spaces where lives are saved

2) Conceived as spaces of control where all aspects of the refugees’ lives are supervised by other institutions

3) Depicted as spaces of destitution and misery

These preconceived notions on how refugee camps are usually portrayed in the media have to be understood and taken into account before being consciously and carefully separated from the intended spatial and urban analysis of refugee camps.

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp, Al Mafraq, Jordan

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp, Al Mafraq, Jordan

Urban Transformers

In his book From Camp to City, architect Manuel Herz starts his text by emphasising the fact that in recent years refugee camps are gaining prominence in the fields of spatial studies and social sciences. However, there is still little understanding and knowledge of such spaces in the disciplines of planning and spatial practices. (Herz 8) The nature of refugee camps as spaces of control and exception is comparable to other authoritarian spaces such as prisons, worker camps and gated communities. The differences between them remains unclear but the examples mentioned above have had their fair share of analysis from the eyes of urban designers and architects to the extent of having a prison design competition conducted by “Combo Competitions” in early 2016.

The Italian Philosopher Giorgio Agamben claims in his book Homo Sacer that camps are becoming a bio-political paradigm of the west. He further defines the camp as “…the space that is opened, when the state of exception begins to become the rule. In the camp, the state of exception, which was essentially a temporary suspension of the rule of law… is now given the permanent spatial arrangement…” Herz further analyzes Agamben’s text and the way he’s generalising the camp as the spatial manifestation, and as the central mechanism, of the state of exception which has become to define the political structure of the Western world. He goes on by demonstrating that the same rules and logic of the camp can therefore be identified within holding areas of airports and the banlieues of cities. The bio-political operations of the Western society are active in refugee camps as well as in slums or detention centers, the individual problems that are triggered by each of those cases remain unrecognisable, and the specific nature of a refugee camp seems more opaque than ever. (Herz 9)

Giovanni Battista Piranesi’s Camp Marzio plan revealed that the camp can be understood as an engraved field, etched, layered, and ordered by diverse objects and programs. (Hailey 3) This definition of camp runs parallel with definitions of cities and metropolises. Refugee camps need to be looked at through the eyes of an urbanist in order to determine if the camps contain qualities of the urban. To achieve that, the vocabulary used in the framework of refugee camps needs to be shifted from one which revolves around technicalities, towards one that understands settlements as environments having urban qualities. Camps act as “urban transformers”, changing the lifestyles of the refugees from a rural background to an urban one. Many refugees do not go back to their rural villages, but resettle in major cities when they return home, thus these camps can be seen as motors of urbanisation. (Herz 19)

Nyarugusu Refugee Camp, Kasulu, Kigoma, Tanzania

Nyarugusu Refugee Camp, Kasulu, Kigoma, Tanzania

Places of Control and Exchange

Herz draws on definitions of “cities” from different thinkers such as the American sociologist Louis Wirth who defined life in a city as a “…life based on abundance and multiplicities of exchanges, meetings, and connections between people that do not rely on personal acquaintance and that end up allowing for social, economic, and cultural mobility.” He argues that refugee camps on the other hand are the antithesis of cities and are described as places of exclusion and complete control. They are places where people have no control over their own lives. (Herz 489) This however, is not a conclusive statement about camps and cities being unrelated.

In his 1977-1978 lecture series at the College de France, published as Security, Territory, Population, Michael Foucault argued that the history of the city cannot be divorced from the notion of control. In presenting cities from different time periods as examples, Foucault states that city planning is seen as an instrument for consciously controlling the flow of people and merchandise within the city, as well as to and from, with the aim of “maximizing the good circulation by diminishing the bad.” (Herz 490)

Cities have always been places of exchange, providing the potential for independence and enabling movement. In most cases this exchange has been carefully controlled, whether by the gates and walls of the medieval city, the introduction of permits of residency and civil registration offices in the early modern era, or the installation of CCTV equipment in the contemporary city. (Herz 490) Camps are consciously employed as an instrument to achieve self-reliance, self-control, social exchange, and mobility, eventually to be realized permanently in the homeland or in the camp if it becomes permanent. (Herz 491)

Herz observed that the difference between the public and the private in the Western world has been increasingly diluted. Public spaces have become more controlled and restricted by private institutions. The erosion of these two qualities (public and private) becomes critical. “The alleged openness of our metropolitan life only exists in response to, or as a result of, enclosures, limitations, and areas of controlled access.” (Herz 491) The Sahrawi camps that Herz studied are living examples in which this controlled access has been turned around and enabled a project of social liberation and political autonomy. He concludes by emphasizing the symbiotic relationship between the camp and the city: “Rather than being binary opposites, the city and the camp can be described as conditions that are always contained within, and necessitate, each other.” (Herz 491)

Herz concludes his text by stating three reasons on why camps are relevant to the urban design discourse:

1) The planning guidelines of the UNHCR are efficient and effective as immediate response to asylum seekers, but limited in grasping the larger connotation of the human condition, with its social, cultural, economic, and political dimension.

2) Having exactly the same starting conditions (geography, topography, ground condition, and climate), difference and specificity start to emerge.The development of difference and specificity gives birth to urban identity.

3) The discipline of architecture and planning is involved in a condition of tension and conflict and often in a contextual vacuum which can be described as “ground zero” of the profession.

Panian, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Panian, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan

Planning Camps

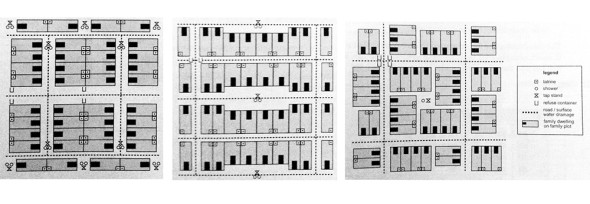

Planning camps usually starts off by organizing units in a rigid-military grid due to quick setup procedures and high degree of control. However, this approach will also depend greatly on the topography of the site chosen to be designed on. There are several planning strategies that camps fall into but they are all forced on the camp in its infancy stages and change overtime,, or adapt poorly to the evolution of the asylum seekers’ lifestyles. In the guideline book entitled Transitional Settlement: Displaced Population there are several suggested planning methods that depend on location, services provided and other technical issues.

The default grid plan decreases cultural connection among occupants and is not environmentally effective; the straight lines of the grid plan often act as dirt funnels and increase erosion of local resources. In addition, this type of planning is not ideal to negotiate local context, especially when in most cases these contexts have harsh environments.

Cluster planning, on the other hand, arranges infrastructural elements such as roads, electricity and water in a tree like arrangement spreading out from a unified core. The core will house the shared facilities such as offices and healthcare. This type of planning avoids some of the adverse environmental effects that the grid arrangement has and gives its occupants more freedom and responsibility to adapt their neighbourhoods accordingly. It can also be integrated and adapted to topography easier than grid planning.

Staggered square plan, community road plan and hollow square plan

Staggered square plan, community road plan and hollow square plan

Other planning methods can be hybrids or different forms of grid and/or cluster planning. For example, the staggered square plan is basically a grid that has offsets every specific number of rows and/or columns to avoid the issue of wind tunneling in grid planning. Community road plan is also a modified grid that enables dwellings to have a frontage facing a road and a back facing another dwelling. Lastly, the hollow square plan is a hybrid of both the grid and the cluster plan. It has higher degrees of security and privacy, in addition to maintaining unity for individuals and families. (Corsellis and Vitale 390)

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp

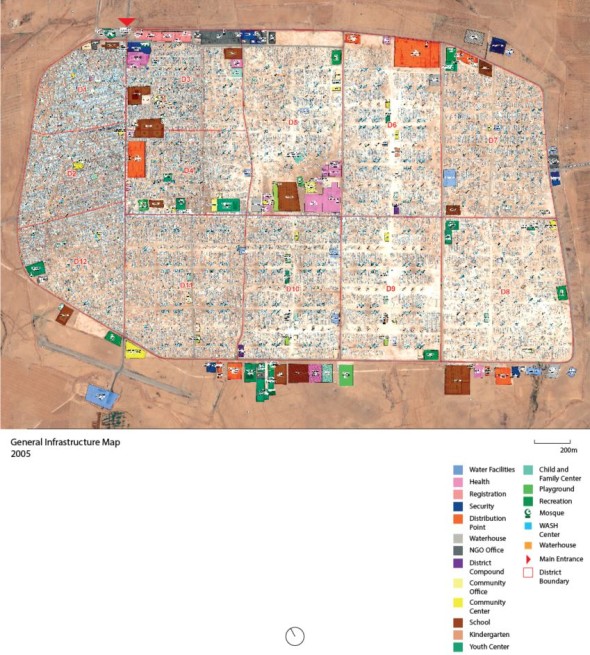

Case Study: Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp

Al-Zaatari Refugee Camp in Mafraq Governate, Jordan, became the second largest refugee camp in the world and the fourth largest city in Jordan in late 2013. The 530-hectare camp costs U.S. $500,000 per day to operate, paid for by the United Nations (UN), partner organizations, and the government of Jordan. (Doucet) As of October 2015, the camp houses 79,284 registered Syrian refugees with 50% male and 50% female demographic. (UNHCR)

The Camp opened on July 28, 2012 as part of the UN-sponsored relief effort to house asylum seekers affected by the Syrian civil war. The conflict between President Bashar Assad (who is Alawite) and the rebels led by the free Syrian Army (who are predominately Sunni) destroyed the fabric of Syrian society in religious, political and economic terms, with the controversial and alleged interference from outside governments and groups. (Eakin and Roth)

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Jordan Hashemite Charity Organization (JHCO) jointly planned and developed the camp on Jordanian armed forces owned land. The original organization of the camp featured housing (tents and later caravans) placed in a grid plan arrangement with rows running in the West-East direction that contain fire access lanes and sanitation infrastructure. Syrian refugees then rearranged the housing units (tents and caravans) to create U-shaped and courtyard complexes that function as compounds for extended families. (UNHCR)

General Infrastructure Map, 2005

Dwelling Units

There are two types of Dwellings in Al-Zaatari – the caravan, a prefabricated modular dwelling, and the tent. Many shops are constructed out of the same modules used for housing. Caravans were introduced later when the displacement lasted longer than expected and more stable housing solutions were required. A caravan is allocated for 6 people. (Laub and Daraghmeh)

Tents

Tents

Caravans arranged in a grid

Caravans arranged in a grid

Commercial Space and Open Space

The camp’s residents sell caravans that they do not need and in turn these caravans are converted to shops where buyers do trade and sell merchandise in the camp. The “Champs-Élysées” is Al-Zaatari’s main shopping street and was formed organically by the residents. It houses anything from meat shops and bakeries to cell phones retailers. The goods are obtained both legally and illegally. Legally by using permissions to visit the neighbouring city of Mafraq to trade and buy merchandise, and illegally by paying off water-truck drivers and other servicemen to smuggle goods into the camp.

As refugees settle into the camp, they convert many spaces into private open spaces, featuring fountains and courtyards paved with cement. The key type of open space is a football field.

“Champs-Élysées”: Al-Zaatari’s main commercial street

“Champs-Élysées”: Al-Zaatari’s main commercial street

Legal System and Power Structure

The camp contains both formal and informal components in its legal system. The camp manager is Kilian Kleinschmidt and a series of informal leaders run a parallel legal system within the camp. There are seven major tribal leaders, or “chiefs”, that had great influence in their hometowns and retained this influence when they moved to Al-Zaatari. Informal leaders control key streets and are known as “street leaders”. Informal leaders have formal responsibilities in the camp such as deciding who will receive a caravan and who will receive official camp employment. (Laub and Daraghmeh)

Water

Water must be trucked into the region to supplement water available from the local aquifer. The Agency for Technical Cooperation and Development (ACTED), in partnership with The United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), is the main water provider. In November 2013 the water consumption was 15.1 million liters daily. The majority of the camp’s residents used to access water through communal water tanks and taps. Camp residents often take components from public toilets such as water tanks, to their private households. (Tran)

Electricity

The United Nations funds, installs, and maintains the electricity used for streetlights and other key infrastructure in the camp. The locations of streetlights pose safety and economic concern, since as of November 2013 an estimate of 73% of the camp have illegally tapped the streetlight grid for private electrical connections. The illegal electricity hook-up to the camp’s residents is usually a point of dispute and has generated problems for camp organizers. In some cases the camp’s residents used trenches and concrete walls to hide the connections from the camp organizers. (UNHCR)

In 2014, the UN paid for all costs associated with electricity at roughly U.S. $500,000 per month during the summer and U.S. $700,000 per month during winter. (Laub and Daraghmeh)

Waste Disposal

The camp lacks a sewer system and is designed for residents to rely on common blocks of latrines for their sanitation needs. However, by the end of 2013, roughly 60 to 70% of residents had built in-home pit latrines that could be individually pumped, or dug out, generating drainage and sanitation challenges with the rainwater runoff system. This led to poor sanitation around the camp, and the facilities lack to contain sewage resulted in standing gray and black water. (Kleinschmidt)

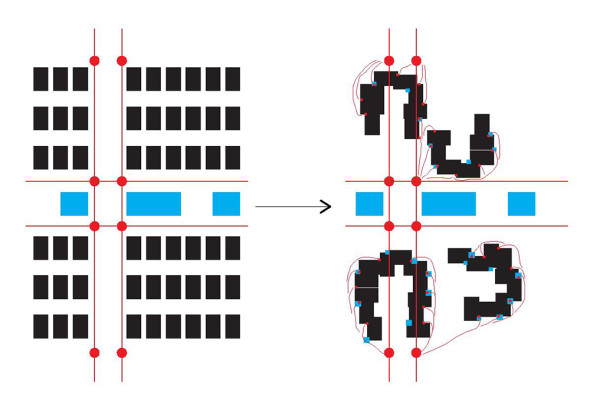

Changes under the effects of illegal utility hook-ups (blue: water, red: electricity)

Changes under the effects of illegal utility hook-ups (blue: water, red: electricity)

Lesson from Al-Zaatari

The initial grid-like arrangement rapidly changed into U-shaped compounds that erased the North-South connection while maintaining the West-East connection. This can be attributed to the fact that permanent structures such as water tanks, communal kitchens and bathrooms are all arranged along the West-East axis with a number of main North-South routes connecting them. Syrian refugees at the camp came predominately from Daraa, which is located south of Syria, where they follow tribal culture. This played a role to why Syrians decided to abandon the row-like structure of the camp and adopt a U-shaped-like compound structure. In Syria, they lived in courtyard compounds with extended families and they were accustomed to living communally and to sharing a courtyard with their relatives. Moreover, the already mentioned, informal power structure of the camp replicates the tribal tradition of the refugees, which is also why they tend to settle in clusters of compounds that are under the jurisdiction of a certain street leader.

As Daraa’s traditions forbid shared bathrooms between males and females, refugees all opted to “move” bathrooms and latrines to the vicinity of their tents or caravans. By doing so, they tried to orient the compounds parallel to shared kitchens and bathrooms.

Illegal utility hook-ups to water and electricity supplies are the main reasons for the grid maintaining its West-East connection and losing its North-South connection.

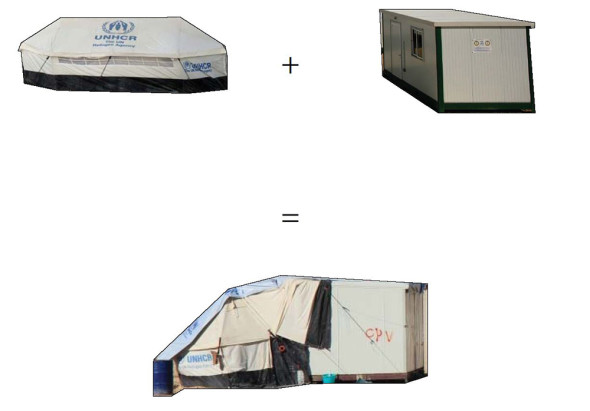

Not only the overall plan of the camp, but also the dwelling typology has progressively changed. Refugees started off with tents and then were given caravans. However, due to the limited size of the caravans and the high number of family members, camp residents started hybridizing caravans and tents to create dwellings larger in size and more accustomed to their living habits.

Typological hybridization

Typological hybridization

Semipermanence

Architect Eileen Gray’s work on luxury campsites and temporary structures addressed the issue of semipermanence of camps. Her work questions what happens when camping methods become fixed and how the camp’s spaces —open and closed, internal and external—are then affected. (Hailey 8) This also applies to refugee camps once they adopt a permanent urban form with temporary rules and regulations. If refugees have the chance and means to go back to their home countries, the camp can either be inhabited by the host community or disassembled and parts of it reused in setting up new camps. In many cases, camps have a good chance of surviving and becoming permanent cities. Energy and resources are spent on setting up camps, which calls for a designed and functioning urban condition that will survive well beyond its “temporary” lifecycle.

Refugee camps deserve to be treated as urban projects designed by urban designers and architects. The case study proves that the original design of these camps fails to address the complexities of a rapidly developing city and the nature of adaptation by the camp’s residents. A prospective design and strategy in both the urban and the architectural sense would prove more successful than the current quick-relief strategies adopted by the UNHCR. The agency for a consciously-strategized design of a refugee camp is present and demonstrated through numerous examples of camps that have survived for decades becoming slums and failed urban conditions.

References

ACTED. Za’atari: At a Glance. “ACTED”, 2013.

Corsellis, Tom, and Vitale, Antonella. Transitional Settlement: Displaced Populations. Oxford: Oxfam GB, 2005.

Doucet, Lyse. Life in Zaatari – Jordan’s Vast Camp for Syrian Refugees. “BBC”, 2013.

Eakin, Hugh, and Roth, Alisa. Syria’s Refugees: The Catastrophe. “The New York Review of Books”, 2013.

Hailey, Charlie. Camps: A Guide to 21st-century Space. Cambridge, MA: MIT, 2009.

Herz, Manuel. From Camp to City: Refugee Camps of the Western Sahara. Zürich: Müller, 2013.

Kleinschmidt, Klein. Interview with Conner Maher. “Interview by Conner Maher”.

Laub, Karin, and Daraghmeh, Mohammed. Zaatari, Syrian Refugee Camp in Jordan, Slowly Becomes a City. “Huffington Post”, 2013.

Ledwith, Alison, and Smith, David. Zaatari: The Instant City. Boston. MA: Affordable Housing Institute, 2014.

Maher, Conner. A Stake in the Ground. “ICON”, Mar. 2015.

Mansell, Claudia Martinez , Camp Code. “Places Journal”, April 2016.

Maqusi, Samar. Spatial Violations: Beyond Relief inside the Palestine Refugee Camps. “SamarMaqusi”.

Tran, Mark. Jordan’s Zaatari Refugee Camp Mushrooms As Syrians Set Up Shop. “The Guardian”, 2013.

UNHCR. Mid-Year Trends, June 2015. “Mid-Year Trends”, 2015.

UNHCR. Syria Regional Refugee Response. “Data UNHCR”.

Author

Aziz Bahou is a Master of Architecture candidate at the John H. Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape, and Design at the University of Toronto. He is currently writing his thesis entitled Semipermanence: A case for a strategized design of refugee camps.

Related Posts

Questo sito usa Akismet per ridurre lo spam. Scopri come i tuoi dati vengono elaborati.

Lascia un commento