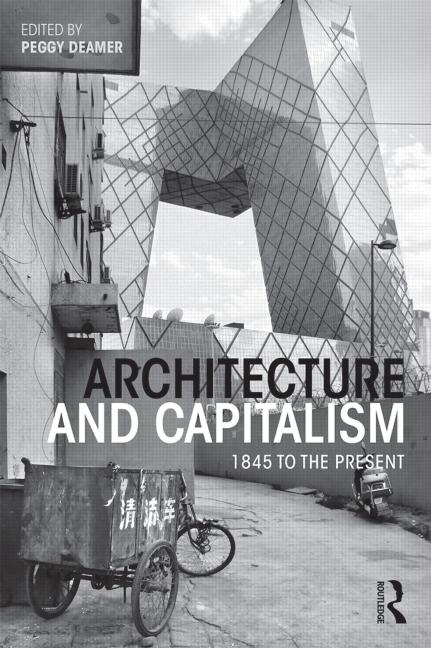

Architecture and Capitalism

From Peggy Deamer’s introduction:

Because building costs so much money, construction – and within it, architecture – necessarily works for and within the monetary system. One could say that history of architecture is the history of capital. But, while this is obvious, architectural history, especially as it is handed to us in the US, is oddly devoid of examinations of this relationship.

[This book] starts from the position that this relationship is rarely direct; that the economy at a given time and place sets the stage for certain cultural productions to be desirable, with architects acting out their design positions accordingly. […] Heinrich Wolfflin […] was wise in pointing out that certain periods of history can only “see” in certain ways, having no consciousness of alternative organizational, visual, or formal schemas. He certainly did not link the circumstances defining these limits to the economy, but he lays out the condition that we wish to pursue here: that it is our cultural desires that shape what architects talk about and see. This anthology suggests that capitalism, in different ways, in different cultures, and in different historical periods shapes those cultural desires and, indeed, makes those desires so desirable that they often seem to fill natural needs.

Another way of saying this might be that this anthology assumes, in the Marxist distinction between base and superstructure, that architecture operates as much in the superstructure as in the base. While the construction industry participates energetically in the economic engine that is the base, architecture (particularly as a design practice) operates in the realm of culture, allowing capital to do its work without its effects being scrutinized. […]

If all of architecture is a manifestation of capital, what forms the selections in this anthology? The first consideration, the time frame and sequence, is determined by the advent of industrial society and with it, the self-conscious awareness of the working of capitalism. […] Capitalism is an instable phenomenon – what it is and how it operates changes constantly and not just via movements between bull and bear markets, recessions and expansions, laissez-faire advocay and regulation, but in its relationship to culture and power. If, as was mentioned above, the connection between capital and architecture is indirect, it is also nimble and mutant. The chronology is essential to grasping capitalism’s changing character and, hence, its changing relationship to architecture.

The second consideration, the determination of what constitutes “architecture”, is more dicey. Certainly, architecture excludes the world of construction that excludes architects; that is, it excludes those developments that are guided by a profit margin unable or unwilling to pay for professional architectural services. It also excludes the larger category of urban development that is so closely tied to politics and economics that it, again, would be a history of the built environment everywhere. Indeed, these chapters adhere to projects and productions that are, for the most part, squarely in the pantheon of “architecture history”, the aim being to re-examine old stories, filling in information regarding the effects of the economic context. […]

The third directive is to follow case studies rather than fill out general periods of architectural history. While this precludes comprehensiveness, it allows the specifics of the relationship between capital and architecture to be examined more closely. […] The “subject” of architecture, like that of capital, is not stable, and the specificity of the case studies is instrumental in covering the various and differing ways in which economics affect architecture. In some cases, the architectural issue is labor; in others, it is affordability; in others still, image and propaganda. […]

Clearly, this book, while about capitalism, is indebted to those who have devoted themselves to its critique, Marx in particular. As analyses of capitalism’s multifarious modes of operation, Marxism, neo-Marxism, and the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School has informed the terms by which this editor and a number of the authors understand the subject-matter. […] The hope is that this anthology will open up debates about the relationship of architecture and capitalism that include non-Marxist orientations.

Contents

vii. Notes on contributors. xi. Timeline. xxxi. Preface [Peggy Deamer]. 1. Introduciont [Peggy Deamer]. 8. Straight lines or curved? The Victorian values of John Ruskin and Henry Cole [Robert Hewison]. 25. The first Chicago school and the ideology of the skyscraper [Joanna Merwood-Salisbury]. 50. The display window as educator: the German Werkbund and cultural economy [Lauren Kogod]. 71. Capital dwelling: industrial capitalism, financial crisis, and the Bauhaus’s Haus am Horn [Robin Schuldenfrei]. 98. Big work: Le Corbusier and capitalism [Deborah Gans]. 115. The varieties of capitalist experience [Simon Sadler]. 132. Manfredo Tafuri, Archizoom, Superstudio, and the critique of architectural ideology [Pier Vittorio Aureli]. 150. Irrational exuberance: Rem Koolhaas and the 1990s [Ellen Dunham-Jones]. 172. Globally integrated/locally fractured: the extraordinary development of Gurgaon, India [Nathan Rich]. 189. Spectacular failure: the architecture of late capitalism at the Millennium Dome [Simon Sadler]. 202. Coda: liberal [Keller Easterling]. 217. Afterword: architecture without capitalism [Michael Sorkin]. 221. Index.

Info

title > Architecture and Capitalism. 1845 to the present

author > Peggy Deamer (eds.)

publishing house > Routledge

pages > 229

year > 2013

price > $44.95

Related Posts

Questo sito usa Akismet per ridurre lo spam. Scopri come i tuoi dati vengono elaborati.

Lascia un commento