Madrid: a tale of two cities

massa critica | davide tommaso ferrando

Following the example of Domenico di Siena, I have decided to publish the text I wrote some months ago for the book The Kent State Forum on the City: Madrid edited by Paola Giaconia and Eugenio Pandolfini (to whom I am grateful for inviting me to take part in this project) and published by dpr-barcelona in the very interesting format of a multi-platform project: Book + Web + App.

Ecosistema Urbano | Eco Boulevard in Vallecas © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

A critical analysis of the public spaces realized in Madrid during the last decade shouldn’t prescind from the observation of the disparity with which the central core of the city has been taken care of, if compared to the less fortunate, newly built neighborhoods. A disparity which is not at all quantitative, as important amounts of money have been invested both in the center and in the outskirts of Madrid (at least until the explosion of the financial bubble in September 2008, an infamous date to which we should also add a small “tail” of public investments, known as “Plan España”, promoted by the Zapatero government in 2009 in order to impulse the private sector through public works), but still a disparity – of method, instruments, goals and results.

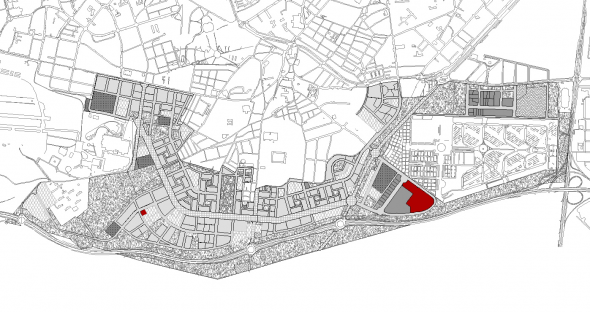

The PAU of Carabanchel with, in red, the location of commercial activities

While, in fact, the offer of leisure spaces was rapidly increasing in the frame of the historic city, thanks to the creation of a strategic network of pedestrianized streets and squares (among which I would like to mention the “shopping parkour” composed by the urban sequence Callao – Preciados – Sol – Gran Via – Fuencarral – Serrano), the new residential neighborhoods (Carabanchel, Sanchinarro, Las Tablas, Vallecas, etc.) were growing deprived of the essential network of places and services that are capable of generating minimal conditions of urban interaction.

Ecosistema Urbano | Eco Boulevard in Vallecas © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

In this sense, it is paradigmatic that the most recurrent “public” feature of these new residential settlements is the shopping mall: a typology that, thanks to its hyper-dense offer of commercial services, usually ends up stealing the role of social attractor from the streets and squares of its neighborhood (the buildings of which, not incidentally, are often designed without spaces for commercial functions on the ground floor). As a foreseeable side-effect of such a short-sighted planning strategy, the streets of Madrid’s new residential neighborhoods are usually underused, if not deserted, as they leak those elements that make urban spaces worth to be lived.

Ecosistema Urbano | Eco Boulevard in Vallecas © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

The only exception to the rule seems to be the Eco Boulevard in Vallecas (Ecosistema Urbano, 2007), whose climatically-controlled cylindrical pavilions, sequentially disposed along the central axis of what should soon become a tree-lined boulevard, give to the inhabitants of the ensanche three unusual public structures open to programmatic reinterpretation: a punctual bless in the middle of a desolated urban context.

Francisco Mangato | Dalì Square © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

A completely different story characterizes the transformation of the central core of the city, which in the last years has been the object of a variety of interventions of “ urban acupuncture” – from the reuse or ex novo construction of a single building, to the refurbishment of a street or square, to the reorganization of an entire system of blocks –, meant not only to improve the image (often degraded or uncertain) of some strategic places of Madrid, but also (and especially) to give their use back to the citizens. Common feature of all these projects is the establishment of a critical dialogue with the existing conditions: a dialogue that, instead of being resolved timidly or mimetically, is often approached by means of three different strategies, depending on the case: collision with the new; declination of the past in contemporary terms; celebration of the existing through minimal interventions.

Estudio Andrada | Iván de Vargas library © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

A good example of the first case is the requalification of the Dalì Square (Francisco Mangado, 2005), a huge, empty space in the middle of the city, the exaggerated scale of which has been brought to a human dimension thanks to the insertion of eleven trapezoidal landscape surfaces in the middle of it, which create a picturesque sequence of smaller (and therefore easier to use) public areas. The geometrical reassessment of the whole complex has been obtained through a regular pattern of light strips carved into the pavement, which cross the square transversely and envelope, when intercepted, the existing volumes of the underground parking entrances, transforming them into prisms of light. Unfortunately, the state of preservation of the square is quite deplorable, as many elements (such as the glass boxes that lead to the undeground parking) have been damaged by citizens, while romboidal boulders have been added to the landscape surfaces in order to prevent skaters from using them.

Estudio Andrada | Iván de Vargas library © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

The Iván de Vargas library (Estudio Andrada, 2010) belongs to the second case. It is a project that rises in extremely delicate conditions, as it faces the baroque church of San Miguel and occupies the plot of the former residence of the Vargas family – a protected building realized in the XII century and partially demolished in 2002 due to safety reasons. The design, without renouncing to express its own contemporaneity, takes advantage of the contextual conditions, reinterpreting the typological implant of the former building in its floorplan, slightly rotating its alignment in order to reveal a new view of the church from a nearby street, and opening itself towards the church through a big, windowed void, elegantly carved in the main facade.

Arturo Franco | Intermediae © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

To the third and last case belongs the transformation of one the wings of Madrid’s former slaughterhouse in a cultural center (Arturo Franco, 2006): a project that shows how results of great value can be achieved with an extremely reduced budget (around 120 euros/sqm). Here, the poetic strength of the design comes from the inspired mise en scène of the historic stratification of the hosting building – an abandoned warehouse, partially degraded. Reduced to a minimal number of interventions, the project underlines the raw materiality of the Matadero through a delicate contrast with the new elements, which become the supporting actors of a diachronic narrative centered on the memory of the original building. In this way, the project doesn’t just give back the spaces of the Matadero to the citizenship: it also reveals its history to them.

Arturo Franco | Intermediae © Davide Tommaso Ferrando

It seems therefore clear, even in such a shortage of examples, how that of Madrid is, at least today, a tale of two cities: the central one, diverse and pulsing, which offers a progressively bigger amount of its places to the creative use of both citizens and tourists; and the peripheral one, repetitive and marginal, which seems to have been planned just to gravitate around the former, if not around the interests of few private investors.

Davide Tommaso Ferrando

Questo sito usa Akismet per ridurre lo spam. Scopri come i tuoi dati vengono elaborati.

Lascia un commento