About Archipelago Town-lines

massa critica | conrad-bercah davide tommaso ferrando

Some weeks ago I was contacted by conrad-bercah, architect and writer based in Milan and Berlin, who has recently published Archipelago Town-lines: the first app entirely dedicated to urban theory. He explained his project to me and proposed to review it on Zeroundicipiù. Unfortunately, as I am not the happy owner of an iPad, I found it quite hard to understand what this was all about, so I proposed him back to write a short, introductory description of the content of the app, and then to be ready to answer some questions that I would have asked him after reading his text. What follows here is the – to me, very interesting – outcome of our written confrontation: a series of challenging thoughts regarding architecture, urbanism and the relation between the two disciplines. Starting from a critical reading of some of the most seminal theories of the XX Century (from Rossi to Aureli, no one is safe here), conrad-bercah proposes to look at the urban phenomenon from a radical point of view: one that involves resorting once more to the gestaltic figure of the “archipelago”, although in a different way from that proposed by Ungers’ Die Stadt in der Stadt, and using cities such as Venezia and Berlin as models for overcoming the state of crisis of contemporary urbanism. Just like all (radical) theories, that of conrad-bercah presents – as far as I am concerned – both moments of thoughtful understanding as well as critical points. But isn’t this, precisely, what all theories should be about: offering discourses that are capable of disclosing new points of view, but that are also open to further elaborations? (Davide Tommaso Ferrando)

Please state the main goal behind your app Archipelago Town-lines.

Archipelago Town-lines is the first installment of an app trilogy entitled MMM Street Trilogy. The trilogy is a collection of notes, texts, videos, street reportages, photo galleries, and interactive data visualizations about urban matter as it has been shaped since the beginning of the MMM (the third millennium). I like to say, half-jokingly, that it is a trilogy from the street, for the street, about the street, remembering that the English expression ‘What is the word on the street’ matches the Italian ‘cosa dice la piazza?’ Since the piazza is now dead, victim of the virtual revolution, perhaps it is better to concentrate on the street, or on what it has become.

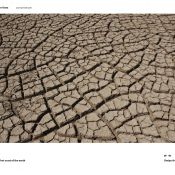

Archipelago-town is a term I’ve coined. The two words it joins are important and are used in their etymological sense. I started thinking about them when I realized that everybody keeps using the term ‘city’ without realizing it has lost its original meaning. What the present scenario actually shows is a ‘pornographic’ picture in which the difference between ‘urban’ and ‘non-urban’ is blurred—I say ‘pornographic’ because the increasing sprawl eating away at urbanity is, to me, just that.

The semantic confusion about the term ‘city’ is, in my judgement, the reason why there hasn’t been a convincing theory about the problem of urbanization for a long time. Words have weight. The word ‘archipelago’ is very popular today, and it is often misused. So for clarity’s sake, let me say that an archipelago is a cluster or a collection of islands. The word ‘town,’ instead, according to an etymological survey, was coined—in most North European languages—to identify a built or unbuilt space, defined by a fence or ‘town.’ That makes origin of the word, which is different from the way it has progressively been used, quite interesting and gives it a built-in, not as yet fully expressed potential that could be essential in defining ‘limits’ and ‘distances,’ the two key concepts on which an archipelago is formed. It might also be useful in distinguishing the built from the unbuilt. For me, ‘town’ coincides with the German ‘Zaun,’ which is to say, fence.

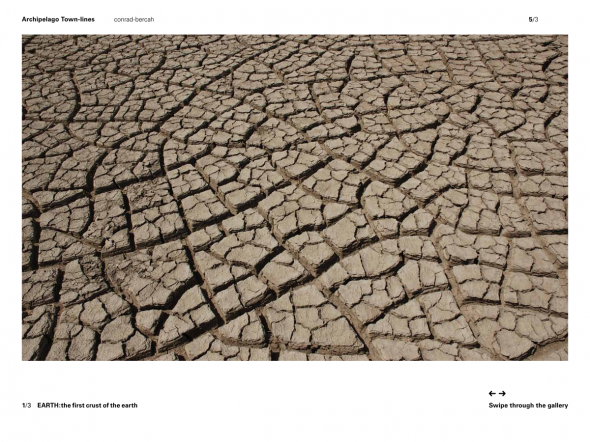

The term Archipelago-town is an attempt to come to terms with the issue my app concerns: the criminal sealing of soil that is taking place in most of the world. It is a frightening phenomenon that, in a catchy sentence, can be described as the UM_urban meltdown, another term I’ve coined. The UM is the phenomenon characterized by the wide spread passion of the ‘silent minority’ that seems to think that there’s no limit to the space available for all sorts of crazy structures. In a way, the UM is just a reflection of the financial meltdown in which everyone in the financial world assumes they can indefinitely sell a limitless number of crooked products to human beings as well as replicants dwelling on Saturn whose main goal in life is to purchase CDO, CDU, or what not. I find the UM to be the most pressing issue of our time for two reasons: the speed at which it is being implemented and the general neglect surrounding it. That’s why I’ve decided to suggest, in a set of notes, a new kind of urbanism that I call Bare Urbanism, a planning concept that addresses both urban growth and degrowth based on the gestalt power of the notion of the archipelago.

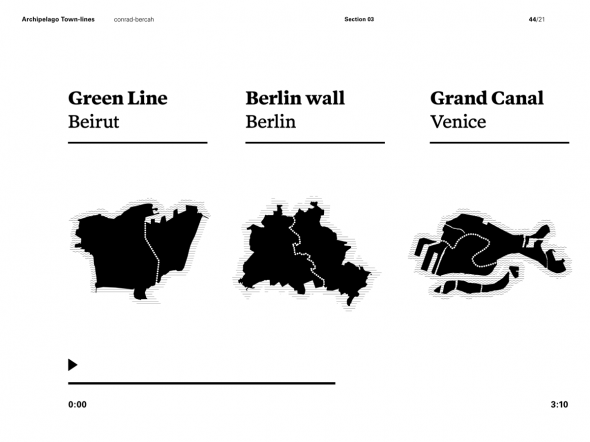

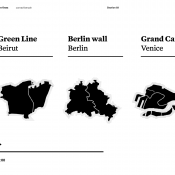

The app, Archipelago Town-lines, is built around three street reports from three different symbolic cities—Berlin, Beirut, Venice—in which I spent a significant amount of time between 2009 and 2012, analyzing and studying their hidden urban and social qualities.

‘The difference between tourist and traveler,’ wrote Paul Bowles in the Sheltering Sky, ‘is that the former accepts his own civilization without question, while the latter compares it with the others, and rejects those elements he finds not to his liking.’ Archipelago Town-lines grew out of a similar mind frame. My travel notes attempt to design a new urban geography that allows the ‘reader’ the freedom to create their own temporal and cultural connections traveling between the past and future of their cities.

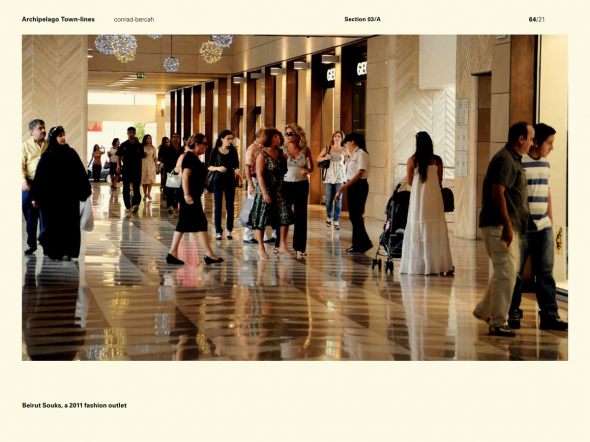

The theory of the Archipelago-town is defined by comparing two urban models: that of Beirut (Hedonistic) and that of Berlin (Romantic). It’s a planning concept that suggests we ought to avoid the former and embrace the latter in thinking about urban growth and degrowth. Assuming a concept can be made more evident by showing what it is not, the two opposing models incarnate, in my judgment, the opposite ends of the urban spectrum: the very livable (Berlin) and the very unlivable (Beirut).

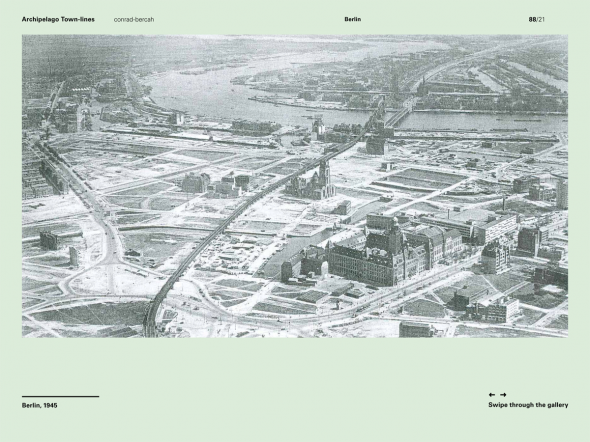

Most people around the world still identify Berlin with the world’s divide. But those who live there don’t perceive this and simply appreciate the fact that urban and social environments can evolve on the enjoyable model I’ve discussed in terms of romanticism—a quality the world seems to have forgotten or overlooked just when it needs it most. I say ‘Romantic’ because, instead of being structured on a dialectic between the center and the periphery, Berlin’s urbanity is made up of a collection (or federation) of towns kept apart by empty, green spaces. The city has grown as a terrestrial archipelago and is governed as such, and its administrative model is yet to be fully appreciated for the provocative logic with which it has established a unique paradigm transcending modernist and postmodernist urban thought alike.

Berlin’s romantic paradigm acknowledges the notion of an urbanity formed by different parts, therein providing ample room for enjoyment, a quality most contemporary urban conglomerations lack. Berlin is a collection of ‘built and unbuilt towns’ each of which has a different nature. Unlike many places around the world, Berlin’s urbanity is built on a plurality of centralities, and in this sense it stands as a unicum, or as a convincing critique of two thousand years of Western ‘rational’ planning. That’s why Berlin, in the urban example it sets, has a role similar to the one Romanticism had in putting an end to the hegemony of the rationalist tradition. There’s a lot to be learned from how this model has developed over the centuries and how it can be implemented in other troubled areas of the world.

The planning concept I suggest in my notion of Archipelago-town finds its archetype (in nuce) in Venice, with the obvious difference that Venice’s empty spaces are characterized by the lagoon instead of the lakes, forests, parks, and varied unbuilt spaces of Berlin. This is why the nine arguments defining ‘bare urbanism’ are called the ‘Venice charter.’ All of these arguments are drawn from the urban model of Venice before it became ‘Venice’―which is to say before the year 1000, the tipping point after which an urban system based on clusters turned into a system of urban stripes.

That of an archipelago-like city is a well-established and influential urban image, proposed in the ’70s by Oswald Mathias Ungers (The City in the City) as a means to solve the postwar urban fragmentation of Berlin by means of formal actions of growth and degrowth (as well as the generic problem of the planning of the contemporary metropolis), and later reused by architects such as Rem Koolhaas (City of the Captive Globe) and Pier Vittorio Aureli (The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture: The archipelago city and its projects) in their works. Also, even if not directly, the idea of a city made of contrasting parts is clearly stated in the writings of Aldo Rossi (The Architecture of the City) and Colin Rowe (Collage City). What differentiates and what is the relation between your critical discourse and those of the mentioned authors?

I’m grateful to you for asking this question as it allows me to clarify aspects of my app that were perhaps not clearly stated in the first release and that I am currently in the process of rectifying for a new release called Archipelago 2.0. I hope you will allow me some latitude, as there are many things that need to be said in answering your question. The literature you cite is pertinent insofar as, in my judgement, it forms a body of sorts that helps me say, by contraposition, what my argument is not about and what, I could even go as far as to say, we should not be doing in talking about today’s wild urbanization.

With the possible exception of Ungers―but not entirely―all of the above theoreticians now appear to have devoted all their attention (in some cases, to the point of obsession), not so much on a possible model for urban growth or for expanding urbanity but, on the role architecture should have in a somewhat ideal world. None of them has focused on the Stadlandshaft, the landscape of the city; they’ve all concentrated on the ‘Monument’ or what used to be described as ‘monument’ in Western tradition. Aldo Rossi is the most extreme example of this attitude. His repetitive, pointless, disordered, flawed 1966 book reduces urban matter to a binary opposition between the ‘monument’ and the ‘area residenza,‘ which is to say, residential areas to the exclusion of anything else.

Something similar can be said about Aureli’s much more scientically coherent book published in 2011. He reads the work of three ‘visionary architects’—Palladio, Piranesi, Boullée—to theorize a possibility negated by history, or even by the way culture is evolving or has evolved in the last quarter of a century. Aureli is still looking at the possibility of a project for the city brought about by a new found role for architecture defined as an autonomous, political, and formal entity. The fact that he proposes this after having clearly stated that the city has been swallowed by the unstoppable march of infinite urbanization is particularly alarming, as his argument appears to be aligned, almost sixty years later, to Rossi’s arguments, which, it should be remembered, made no sense at all in reference to the way American cities formed or functioned.

Francoise Choay has defined the Architecture of the City as an ‘anthology of nonsense,’ a judgment that, in some way, underlines the book’s strength. It actually is an anthology of singular parts of great interest that, in spite of the author’s intention, do not form a coherent theory, mostly because, in a typical Marxist (and Rossian) fashion, the book aspires to a curious goal: the possibility of defining ‘the city’ as an individual unity, or even architecture as a formal law valid for every urban element. Architecture and the city sharing one individuality, the city being a great architectural manufatto. (It should be remembered that, as Elisabetta Roveri has shown, Rossi’s had intended to title the book Manuale d’Urbanistica, but apparently Paolo Ceccarelli convinced him to change the title directing his attention toward the regional, economical, and social sciences—fields that were not exactly popular in Italy in 1960). Rossi does not concern himself with the issue of the city’s form, and, in fact, he barely says a word about ‘the city’ per se. He concentrates on ‘i fatti urbani,’ without managing to explain what he means by this.

All in all, I think that all of these theories can be summed up curiously by Fabio Calvo’s famous image of Ancient Rome as an archipelago of monuments: a circular fence housing nothing but monuments sitting in a blank space. The Monuments are what it is worth talking about, there’s no need to worry about anything else. This, of course, also applies to Koolhaas’ 1978 reading of the most important ‘islands’ of the Manhattan grid― the Rockefeller Center, the Downtown Athletic Club, the Waldorf Astoria―and I will spare you the absurdity of the ‘abstract’ image (or metaphor) where the grid is the ‘sea’ and the individual plots are the ‘islands.’ Outside of architectural circles, where the misuse of vocabulary is the norm rather than the exception, no one would buy the notion of an archipelago―one of the most naturalistic concepts at our disposal―as a squared affair of squared islands laid out on a squared grid!

Please don’t get me wrong: I am a great admirer of all of the above speculations. I find them daring and moving even today, even if Aureli’s timing is somewhat mind blogging, as it seems to be a product of a different geological era that bears no relation to our times in which private interest has annihilated public interest or, as he himself puts it, ‘human associations are ruled only by the logic of the economy and are rendered in terms of diagrams and growth statistics.’

Aureli’s reading of Mies’ work is, of course, of great interest, as it correctly shows Mies’ main contribution, namely the possibility of having islands of architectural greatness within the sea of urbanization. I think that this is the most important argument of Aureli’s book and that his work as an architect seems to be confirming this absolute, at times despotic, architectural aspiration.

Generally speaking, I would say that all of the aforementioned literature is more interesting in the relationship it bears to the architectural work of its authors, than for the argument itself, which, to be polemical, appears to be same old story repeated over and over again, even if it is approached from a different angle. In short, I would say this sort of blind faith in dogmatic rationalism (that Aureli seems to be pursuing) or in rigid philosophical categories, which somewhat reflect the central core of Western philosophy of two millennia, or the very idea that one all-encompassing, all explaining theory/truth should exist is the very thing that we have now outgrown.

My theory is less concerned with architecture, which, to me, has lost whatever urban role it may have had in the past, and more focused on a planning concept that can be implemented to make urban matter more livable. Or enjoyable. In a way, my argument isn’t so interested in this literature. It comes out of first-hand experience and observation on the field, following a somewhat anthropological method, if you like. To tell you the truth, I didn’t know about Ungers’ manifesto until very recently, when Harry Cobb pointed it out to me in relation to my argument. I read it after I had finished my text, and what I found very interesting was the fact that, after Unger’s own demise, the ‘manifesto’ has become the object new found attention (sponsored mostly by Rem) to credit Koolhaas as coauthor and to situate the book within Rem’s own intellectual trajectory.

My critical discourse criticizes the idea of the archipelago as ‘ the city made of contrasting (architectural) parts.’ As Aureli, in my judgment, correctly underlines, the city and urbanization are two different, competing things, and we know who has won that competition. As I have clearly stated in my book/app, the word ‘city’ is no longer usable, as there aren’t any cities left on the map. The City in the City, The City of the Captive Globe, The Architecture of the City, Collage City, The Image of the City, The Possibility of an Absolute Architecture: The Archipelago City and its Projects. These are all titles about ‘the city,’ even though the city, conceived as an exception to the rule, or as an island of ‘civilized’ urbanity against a sea of wilderness (or uncivilized or urbanized country folks) is long gone.

In othe words, I think we can all agree on a simple fact: we are living in urbanized ‘fields’ unevenly covered by different degrees of wild urbanization. The horizon has changed and so should the speculation. We are rapidly (and thoughtlessly) approaching a Tabula Plena phenomenon, and perhaps it is time to think seriously about some selectively chosen areas, islands of urban pause, applying the not-as-yet implemented (but often evoked) Tabula rasa strategy. This is why my arguments steers clear of the notion of the city or that of ‘repairing’ the city and is based, instead, on the concept of town (Zaun) taking Berlin as a guide because Berlin can be described as a Zaunsammlung or a collection of ‘fences,’ which is to say the etymological origin of the word town.

As I have said before, most of the current urbanization can be called ‘urbanization’ precisely because it shows an unhealthy relationship between public and private spaces or between the natural and the artificial. The notion of the archipelago-town or, if you prefer, the notion of establishing an urbanity as a collection of parts that are different in nature―rather than a collection of monuments or architectural artifacts―is an attempt to find an healthy equilibrium between the open and the closed, the built and the unbuilt, the natural and the artificial. This equilibrium is very evident in Berlin today, even if short-sighted civic administrators are doing their best to annul this stunning, unique quality of the urban conglomeration known as Berlin.

In my book/app I tried to underline the stunning uniqueness of Berlin’s DNA, which is the result of historical and political forces. It is a DNA that has shown remarkable resilience in opposing every attempt at standardization under the aegis of a single principle. Berlin was never shaped by a single idea alone; it is the sum of many that diverge. It is a place in which thesis and antithesis have been given simultaneous expression, remaining side by side. This was made evident by Ungers + Koolhaas’ 1978 Berlin manifesto (recently republished by Lars Muller), even if I have trouble with Unger’s obsession for turning Berlin into ‘a colossal enlargement of Schinkel’s Schloss Glienicke.’

Where our stands differ is that I’m still skeptical of the notion of free-standing, isolated architectural islands within a field of unkept natural landscape, as the first draft of Koolhaas’ manifesto suggests, for the purpose of stimulating new forms of new tourism, like urban hunting safaris! As a far as I am concerned, urban tribes of metropolitan gypsies do not need architectural stimulation to form. In short, my trouble with Unger’s notion of the Green Archipelago is that it remains dogmatic in its formulation and closer to Hans Scharoun’s collective plan of 1946 than he would ever admit. My vision, as the re-publication of the manifesto allowed me to discover, is closer to that of Hermann Jansen, who produced the winning design for the Gross-Berlin development of 1910, with a vision of a closely knit web of green spaces, extending to Potsdam and beyond.

Having come this far afield, I have to underline a few things to conclude.

First: When I finished my text, I asked Valerio Paolo Mosco for some feedback. He directed my attention toward Saverio Muratori’s 1959 book, Studi per una Storia urbana operante di Venezia, which, to my dismay, remains the first to have spoken of the città-arcipelago, a notion somewhat related, but not quite, to my notion of the Archipelago-Town.

Second: The 1977 Berlin Manifestos did not aim, as your question suggests, at ‘solving the generic problem of planning the contemporary metropolis.’ The manifesto’s text was the odd intersection of a Cornell summer school held in Berlin and a proposal that Ungers delivered to the SPD congress on September 23, 1977 to sponsor his candidacy for director of the forthcoming IBA Berlin exhibition. It was not an urban concept for the contemporary metropolis but for the future development of Berlin, which, in the 1980s, was thought to have experienced a 10% population decrease.

Third: Here I cannot fail to underline an interesting overlap. Ungers came to the notion of the Green Archipelago as a strategy driven by the 10% population drop that Berlin was supposed to have experienced in the 1980s. I have come to the planning concept for expanding urbanity using the (albeit different) metaphor of the archipelago, not for Berlin but, as a role model for the rest of the world. And I look at the fact that Berlin is supposed to experience an almost 10% population increase in the next twenty years as a further irony of history. This, to me, is the best proof I can think of that the notion of the Archipelago is one that works both ways. It works for urban growth and for urban degrowth, which is to say the simultaneous phenomenon that is currently characterizing the evolution of urban matter worldwide. This is perhaps the best proof that it is a very undogmatic concept.

Fourth: There is a very important difference between my planning concept and most of the aforementioned examples. The notion of the Archipelago-town is not an idea that is spendable in relation to future expansion alone, it also works with what it already there and doesn’t work. Hence the need for a ‘Nobel project’ for urbanity, which I put forward in the second installment of my trilogy, entitled Dystopic Town-lines, which i will leave on the horizon, for the time being.

In the text, you make reference to the German city’s “romantic” paradigm, where romanticism is a word that takes us back to the XIX Century, recalling ideas such as subjectivity, the experience of history and Gesamtkunstwerk. When proposing the adoption of a romantic urban model, what is it that you exactly mean?

Kein Gesamtkunstwerk der Urbanität, bitte! I am tempted to reply, as my argument can in fact be summed up by this very formula. My speculation tries to avoid all-encompassing formulas at all costs, as I am convinced that urbanity is too complex a phenomenon to be cured by any formula or slogan, like ‘smart cities,’ for instance, or any of the others. My use of the ‘romantic paradigm’ is an attempt to plant a permanent question mark in the path of generalizations or easily spendable (and marketable) formulas. Why? Because I think we are where we are because of the inability of urban planners or architects to accept one simple fact: the evolution of urban matter is a multifaceted, complex, and difficult affair that should be handled with an open mind, free of prepackaged formulas or strategies.

I have a confession to make: For me being ‘ein Berliner’ means, at least chronologically, being an ardent follower of Isaiah Berlin’s work (long before being head over heels about the German Hauptstadt). In general, I think the world be a much better place if people, especially the so-called ‘elite,’ spent at least a day in their life reading any of his essays they can get their hands on.

Isaiah Berlin has pointed out three major turning points in the history of Western political thought. The first took place when the School of Athens (350 BC) ceased to conceive of individuals as intelligible in the context of social life alone and started speaking of them in terms of inner experience and individual salvation. The second was brought about by Niccolò Machiavelli, who recognized that political values were not only different from but also incompatible with Christian Ethics. The third, the greatest (and the last), was due to the so-called Romantic paradigm that managed to destroy the notion of absolute, subjective, and relative truth and validity as such in ethics and politics.

Berlin’s lectures on the roots of Romanticism demonstrate that this movement ended the hegemony of rationalist tradition. For him, the Romantics set in motion a vast, unparalleled revolution in humanity’s view of itself. They destroyed the traditional notions of objective truth and validity in ethics with incalculable, all-pervasive results. ‘The world has never been the same since, and our politics and morals have been deeply transformed by them. Certainly this has been the most radical, and indeed dramatic, not to say terrifying, change in men’s outlook in modern times.’

Isaiah Berlin has convincingly demonstrated that Germany, not England, not France, was the birthplace of the ‘romantic paradigm,’ a paradigm that embraced the unpredictability of life and of nature. The city of Berlin does the exact same thing for me. So I am interested in directing attention toward the possibility of understanding and appreciating the city of Berlin as a romantic paradigm that puts traditional Western planning concepts out their misery by suggesting that we might make the most of the few remaining urban voids rather than just filling them up.

This ‘Berlin paradigm’ suggests that urbanity could become a system of isolated multiracial and individual towns that accommodate all languages. It is a paradigm that reflects the splintering form of contemporary society within its own fragmented fabric. It is a paradigm that suggests that urbanity is a field formed by contrasting parts in a state of permanent incompletion.

Romantic urbanism is, to me, a new urban ‘species,’ or a third sex, as Magnus Hirschfeld would have said. Romantic urbanism is built on the slow spaces (langsame Räume) Sharoun first mentioned in 1946, on spaces in which urban dwellers can nurture their technical, intellectual, or social needs. Romantic urbanism rejects the re-composition of existing conditions and, on the contrary, attempts to make the most of out of them to reinterpret fragmentation. Romantic urbanism is made up of islands of density and islands of sparseness juxtaposed to each other. Romantic urbanism embraces both the desire for stability and the need for instability. It has no ambition of reconciling all ends. It has no ambition of solving all the problems of urbanity, or society. Romantic urbanism is a dialogue between what is fixed and what is unstable and in permanent flux. It reminds one that urban life is not a jigsaw puzzle where all the pieces fit. It reaffirms that the idea that one single, coherent pattern is more abnormal than the normal.

To my mind, the beauty of the metaphor of the natural archipelago is exactly this: It does not refer to an absolute, all-encompassing, infallible model but relies on a gestalt figure that can be adapted to a variety of specific situations that might be useful in making head or tail of the current urban meltdown. The figure of the archipelago is a metaphor, a symbol, and an iconographic model that is helpful in forming a detached understanding of the processes of rationalization and secularization of digital culture. It is a tool that allows us to ‘measure’ the many facets of urbanization as we perceive them and as they could be.

Thinking and designing in metaphors or analogies is nothing more than a transition from a purely pragmatic approach to a more useful mode of thinking. It is a thinking process based on qualitative values rather than quantitative data. This approach is not meant to substitute the quantitative sciences but to counteract the increasing influence of all attempts that claim a monopoly on understanding and action based on the ‘GDP growth model.’

You suggest a parallelism between the territorial conditions of Berlin and those of medieval Venice, proposing the latter as the archetype and model of the Archipelago-town, and using the year 1000 as a watershed after which Venice’s urban form is not to be taken into account. What I find interesting here, although in a problematic way, is that you are proposing to make a planning example for contemporary urban issues out of a tiny and exceptional study-case extracted from a historical period in which Western cities as we know them weren’t even born yet (I am here referring to Marco Romano’s urban theory of the Estetica della Città). Why do you think that medieval Venice is an efficacious and scalable model for today’s mastodontic urban problems?

About a month ago, I presented my app at the MIT Center for Advanced Urbanism. I was stunned to be asked a question that had the following subtext: If I have a problem in China, I have to use a Chinese example and there is no point in resorting to an example set by Venice or Berlin. Do you not agree? I wanted to reply: What about Neo-Palladianism? Or South American cities? Do you mean to say that Jefferson’s University of Virginia in Monticello is not a valid example because it is based on a European model? I held myself back.

Lately, we’ve been bombarded with architectural books overloaded with statistics about the ubiquity of bad urbanization. When I peruse the LSE book The Endless City, or the current MoMA initiative for the ‘Megacity,’ I am stunned by one fact: there is an immense collection of bad data and bad news, or bad examples and no sign of someone having the balls to indicate a possible way out. Since I am interest in being positive rather than negative, I’ve focused on Berlin and Venice because I think they may be good, useful examples of something that works and they could become tools or concepts in dealing with the problem of making urbanization more human or more acceptable.

Up until the XIX century, many world maps portrayed a lot of unknown land or Terra Incognita, an expression that had once often been used to describe the countryside. Today, it seems as though the new Terra incognita is the rampant urbanization surrounding us all. If we start to look at the DNA of this conglomeration, if we start to free it from everything that is unnecessary or redundant, perhaps we can manage to unveil its real disease and come up with a cure. If I refer to Venice before the year 1000, it is because I want to underline a planning concept in nuce. I am not suggesting that we should rebuild pre-1000 Venice. It is the relationships between the different parts of pre-1000 Venice that are interesting, not their actual size, which, of course, has no relation to today’s scene. It is an attempt to describe the hidden DNA of a place by looking at its geometry, a strategy I find more useful than being buried under masses of data or empty graphics.

The scattered urbanity of Berlin’s bezirke is what we should be striving for, and the urbanity of pre-year 1000 Venice is a miniature example from which there is a lot to learn. Berlin is the result of 20 (now 12) bezirke or neighborhoods, and Venice was the result of 30 parrocchie or parishes. The size is different but the principle is the same. Each neighborhood is manageable in size; it is made of a cluster of different urban events, of public and private space, of open and closed areas. It is a physical and an administrative model. Experience has proven that it is not possible to tackle problems at the mega scale. The notion of a mayor for NYC is non- sense. The need to scale problems down to something understandable is essential to creating more manageable living and working areas at the kiez–quartiere–neighborhood scale as well as that of individual buildings.

You define the content of your app as “traveling notes”, implying that what’s inside the app is the result of your first-hand experience of the three visited cities. Could you give a slightly deeper description of the kind of material (texts, graphics, images, videos…) you have collected and put inside the App?

The mostly fake Top Down\Bottom Up dichotomy is perhaps too embarrassing to be quoted, but I have to resort to it because it is one important aspect of my entire project, which is based on personal experience rather than a bibliography.

My app is an archipelago of different travel notes, which can take the form of a photo gallery, a video, an interview, an sms, a journal entry, a text, or even a manifesto I’ve put together over a period of three years. This material has been sifted through and rearranged, in the app, by Studio Folder, an offshoot of the studio formerly known as Salotto Buono, which was responsible for the app’s graphic layout.

I started jotting down notes about these three conglomerations when I lived there and was experiencing different emotions. I found Beirut to be one of the most disturbing places in which I have ever lived, to the point of being unbearable, and I found Berlin to be the most enjoyable place I will ever know, to the extent that I have recently moved there to live and work. Being curious about these different sentiments, I had to investigate what was behind my emotions. So you might say that my app is a very personal and deeply felt operation about cities that I know and with which, for one reason or another, I’ve had to come to terms. In this sense, it is a very bottom up approach that sprang from the experience of the street rather than selected intellectual speculation.

Finally, why did you choose to create an app instead of publishing a book, writing a blog or shooting a documentary? How did this choice influence the way in which you have collected and organized the material? What do you think is gained, and what is lost, in the production of such a kind of editorial project, if compared to “classic” ones?

There are many practical and theoretical reasons. I’m very glad that Studio Folder suggested this venue and that this venue was selected. At the most basic level, I would say that an app gives you a flexibility that is obviously impossible with printed matter, which does cannot accommodate the multimedia components that, given the topic, are essential in reflecting on the complexity of the problem. The app is a dynamic tool that, like the chameleon, can change its skin as time goes by.

Let me give you just two examples. The first is the last section of the app, which features a series of ‘reviews’ in the form of 7-minute-long interviews, in which people who have read the book/app comment on it. It is a section that keeps growing and is stimulating a debate I’m following very closely. The second is that, after a series of public presentations and a number or conversations with interesting parties that allowed me perceive things I did not perceive until they were pointed out to me, I can now add new parts and change others to rectify some things or clarify others that were perhaps taken for granted. So I would say that, for me, the ’classic’ notion of an editorial project is so out of date it’s simply inconceivable.

At the same time, I have to confess that I got tired of waiting for established publishers to (not) find the time to discuss projects. Publishing companies have become (expensive) printing rooms that are (practically all) on the verge of death and are squeezing authors in the process. Luckily, technology has introduced the possibility of self-publishing. It is a hell of a job, but one that gives you enormous control over the process, without wasting paper or gas to move books around. Prices can be kept low, which increases sales and allows you to keep 70% of the selling price. Being close to approaching 10,000 downloads in less than 10 months since the apps release, I think I’m entitled to say it has been a smart move.

There is only one problem, related to the condition of being the first and, as far as I can tell, the only app dealing with these issues. There are no apt ‘Apple App store’ categories to list under, and therefore one has to opt for the ‘educational’ one, which remains, for me, a nuisance.

Gallery

Video

the 3 crusts theory from conrad-bercah on Vimeo.

Related Posts

Questo sito usa Akismet per ridurre lo spam. Scopri come i tuoi dati vengono elaborati.

Lascia un commento